Policy kayfabe

Deep sea mining, minerals processing on military bases, and community benefits

This is the fourth post in Tailings, my series on minerals security in America. Since I’m once again covering specific types of resources, I’ll reiterate that these posts do not constitute financial advice.

Last week’s post addressed permitting as an overstated barrier to US critical minerals production. This week, I’m touching on what I’ll call “policy kayfabe,” where an administration pushes what it frames as bold or transformative action to support an industry, but accomplishes little in reality.

President Trump has done this more explicitly with minerals permitting to demonstrate support for the mining sector. The Biden Administration’s socio-economic initiatives and “raise all boats” messaging produced varying effects across different industrial sectors, but delivered more good feelings than results with critical minerals. If anything, these approaches have diverted resources better spent addressing first-order chokepoints.

Both administrations have pursued their respective policies with too much attention to parochial or ideological interests, giving the appearance of action while not sufficiently addressing industry needs. Much of it amounts to empty signaling.

Let’s dig in.

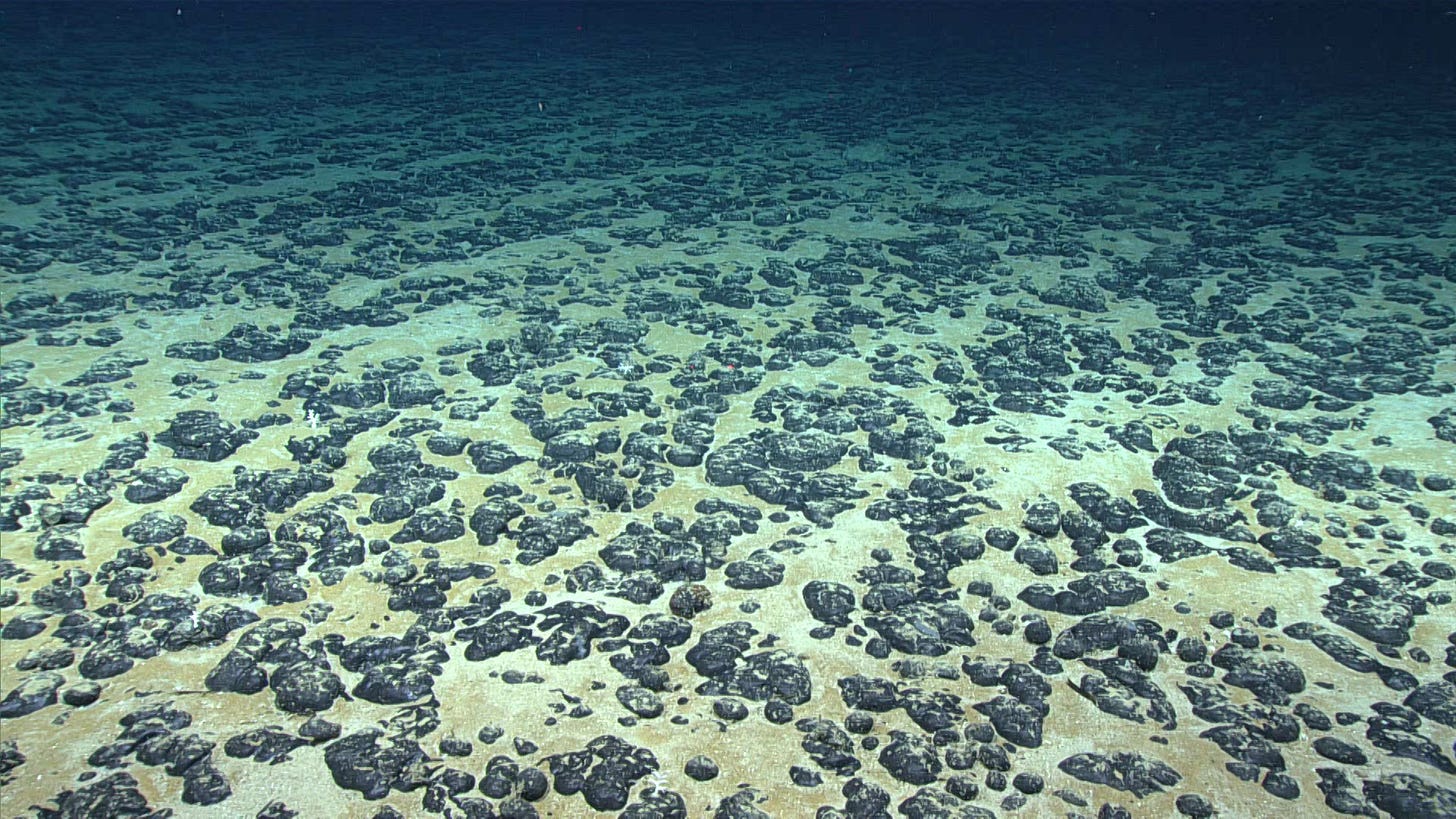

The underwater rock collection

The Trump Administration has made a concerted push to support deep sea mining, with an executive order in April 2025 and action last week by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)1 to accelerate project permitting, effectively circumventing international law.

I’ll just come out and say I’m not a fan of deep sea mining, and it has nothing to do with attachment to international law or environmental concerns. I find it to be a fascination of industry outsiders - tech guys in particular - with no practical knowledge of mining economics or industrial supply chains.

Silicon Valley loves deep sea mining because it relies on breakthrough innovations that “disrupt” the status quo, and purports “massive scalability” on claims of a huge addressable market. And something about scooping little metal balls (nodules) from the ocean floor just sounds cool.

The Trump Administration loves it because Silicon Valley loves it, and because it feels like a “Great Power” competition battlefield with China.

I can’t categorically say American deep sea mining won’t ever produce meaningful metals recoveries, but the logistical and economic hurdles to operationalizing these resources are staggering. I saw pressure within DOE to support deep sea nodule processing in our funding programs, without any real consideration for commercial merit. Hopefully, we don’t see meaningful commercial funding support steered away from more viable resources and processing technologies.

The infrastructure is non-existent to support a fleet of mining ships (which also don’t exist),

The Jones Act would apply if we mine in US territorial waters,

The flowsheets for processing polymetallic nodules have never been demonstrated at meaningful scale, rendering the economics of commercial processing entirely speculative, and

The Trump Administration’s war on electric vehicles snuffed out any attempts at building domestic pCAM production for nickel-based cathodes in the US, all but rendering domestic nickel and cobalt processing to battery-grade sulfates unfeasible and undesirable.

I’ve stopped trying to rationalize market valuations, but this is one of the sillier manias I’ve seen in the sector.

Base-d refineries?

Another genuine head-scratcher is the Trump Administration’s obsession with siting critical minerals refining on military bases. It’s one of those things that sounds like a creative solution unless you actually know how our industrial economy and site selection work in practice.

Typically when siting refinery projects, developers evaluate three broad priorities:

Logistics and geographical alignment

Incentives and costs

Ease of doing business and speed to commissioning

You’re not building a mineral processing plant in the middle of nowhere unless it’s next to your mine. Otherwise you want proximity to suppliers, customers, and the transportation network that minimizes frictions between you and them. And if you’re not co-locating at your mine site, you’re definitely not building a plant without some combination of meaningful state and local incentives, a reliable labor pool, and affordable access to power. Finally, because you may be working with toxic materials, including reagents and waste byproducts, you want to site somewhere relatively permissive from a permitting standpoint.

Which brings us back to the scheme prioritizing critical minerals refining on military bases. I don’t see the point. Free land, a permissive federal government, and (depending on the material) access to your final customer sounds great in theory. In reality, we have no shortage of available sites for small and medium-scale projects—sites that state and local governments prepare precisely to enable industrial facilities.

Now it’s possible the Administration finds some small-scale defense manufacturing chokepoints that it can address with on-site production at a base, but we don’t design military bases around industrial projects in the first place. I find it unlikely they’d be conducive for processing minerals given the requirements of those facilities, let alone stronger candidates than our existing industrial zones. And certainly we don’t want to expose any military living quarters to the more toxic minerals processing facilities that might be more difficult to permit.

How critical minerals refinery site selection works

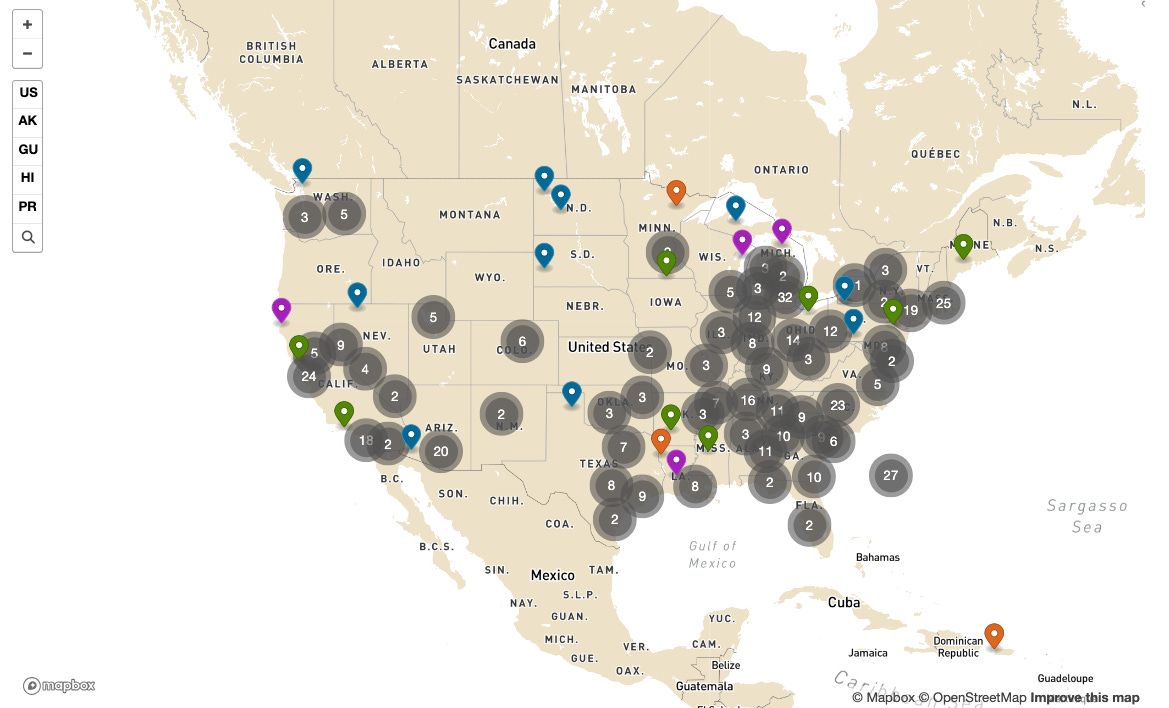

I maintained an open dialogue with state and regional economic developers during my LPO tenure, and was privy to many site selection processes on the applicant (and prospective applicant) side. There’s a reason the same states kept popping up on shortlists—free land, proximity to suppliers and customers, great incentives, growing metropolitan regions with the right kind of workforce, and ease of permitting.

The most competitive states, primarily in the Sun Belt, do a phenomenal job of collaborating with their electric utilities on quick access to cheap power,2 develop both industrial parks and megasites with access to highway and rail infrastructure, and ensure those sites are clear of (or at least designed around) environmental and cultural resources to avoid permitting snafus.

For critical minerals refining, the Gulf Coast has a particular advantage with the petrochemical sector and cheaper access to chemical reagents, as well a proximate market for some waste products. For projects expecting to rely on imported mineral feedstocks, access to key port and river infrastructure presents a significant advantage. I found many projects drawn to the Mississippi River, where they could barge imported materials upriver from the Port of New Orleans.

States can reform their policies to improve competitiveness vis-a-vis one another, but as a nation we have no shortage of attractive sites that offer the benefits military bases purportedly would…without the downsides.

Too much listening, not enough doing

The Biden Administration had its fair share of unproductive policy steers too.

I’d argue its greatest crime was trying to appease everyone, not just various progressive interest groups (“The Groups”), but also industry stakeholders that held implicitly opposing interests. I’m planning to cover the latter when I write about demand signals in a few weeks, but for now will stick to community interests.

Too much stakeholder input, too much fear of upsetting any coalition member. Too many listening sessions and box-checking exercises that aren’t tied to tangible outcomes, or worse, may divert resources from producing tangible outcomes.

I want to separate community-oriented activities into two discrete groups:

Those that are required by law and help deter lawsuits.

Those that go above and beyond what insulates projects from lawsuits.

As I discussed last week, reforming federal statute at the expense of environmental or other protections may enable cost and timeline reductions for the mining sector writ large (though are of little help for critical minerals). But our laws are our laws, and agency activities performed to ensure compliance or reduce litigation risk are not inherently a waste of time or resources. At least at LPO, that was the majority of work our environmental and community benefits-oriented personnel covered.

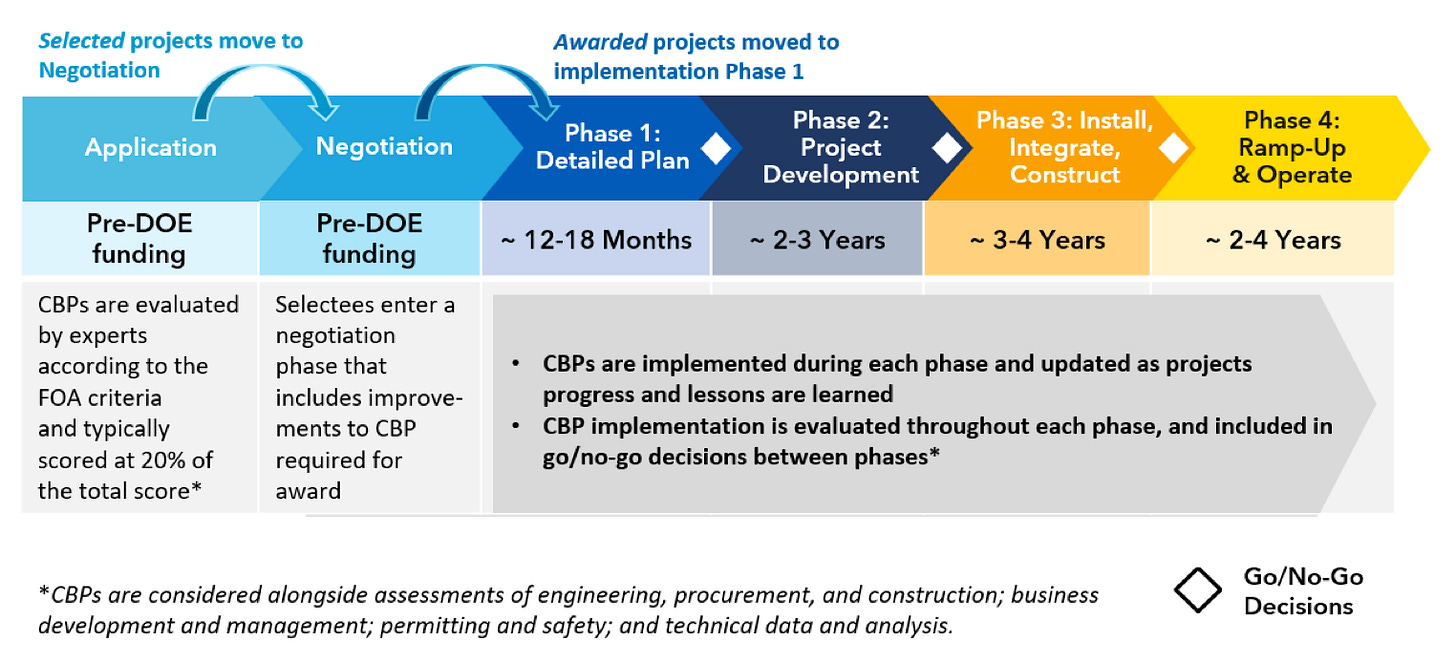

The Biden Administration’s Justice40 initiative3 and associated polices went above and beyond the protections required by statute. The initiative was redistributive in nature, and ultimately required federal funding recipients to commit additional benefits to disadvantaged communities.4 In addition to explaining how their projects would align with Justice40, applicants would, starting in 2023, also have to propose Community Benefit Plans (CBP) with their applications for grants and loans.

I won’t discuss the philosophical merits of Justice40 or CBPs because I’m trying to keep Tailings focused on minerals security objectives, not larger societal values. I also don’t want to make sweeping statements about these policy initiatives across all sectors of the economy. Their effects on $10 billion semiconductor fabs or renewable energy deployments differ from those on critical minerals projects.

Community benefits only exist if there are benefits in the first place

The Biden strategy aimed to make everyone feel like a winner in American re-industrialization, while nudging companies to align with the Administration’s objectives. Despite bad-faith accusations from political opponents, the Biden team went out of its way to not force companies to radically alter businesses practices against their will…or pick winners and losers. I would argue to a fault.

Instead, the Administration attached strings to funding opportunities, in hopes of influencing corporate decision-making. Some of these came via statute—like the CHIPS and Science Act’s (CHIPS) notable childcare requirement, but others it implemented pursuant to early executive orders.

Grant programs would set aside anywhere from 10% to 25% of their scoring weight for social criteria (e.g., Justice40, CBPs, etc.). Less viable project sponsors with good consultants would often craft well-written narratives and check program requirement boxes effectively to compensate for structural project weaknesses.

In theory, sponsors that rose to the Administration’s aspirations were better positioned to deliver projects and successfully operate them. Distribute profits to the surrounding community, you’ll face less local resistance. Invest in local/regional education, you’ll build your future workforce. Sign project labor agreements (PLA) or encourage plant unionization, you’ll more easily source and retain workers.

In practice, these project elements did little to sort viable from non-viable, and cost both time and effort from the applicants and reviewers.

I plan to cover DOE’s battery grants and others in greater detail on the topic of funding, but I don’t believe these social criteria meaningfully weighed on project selection the way they likely did for US Department of Transportation (USDOT) or Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) deployment programs. Instead, they just increased our administrative burden.

The Biden Administration spent too much effort ensuring the hypothetical benefits of projects would be broadly distributed versus ensuring the projects delivered at all.

100% of nothing is…still nothing.

LPO wasn’t immune either. Shortly after I joined, the CBP requirement started creeping into our programs. First these were treated as confidential application documents, then we eventually required applicants agree to publish them. The logic being, in the absence of a legally-binding Community Benefits Agreement, a publicly-stated commitment is harder to walk back than one kept behind closed doors. Publication was also a way for the Administration to show it was delivering for progressive coalition partners (even though projects had yet to deliver).

We thankfully didn’t write CBP terms into loan agreements as covenants that could trigger events of default. Ultimately, most of these commitments were not overly burdensome to projects, and I’d concede they were likely net beneficial if projects actually delivered. But I found the appeasement of organized labor in particular to be excessive and potentially counterproductive to industrialization efforts. PLAs locked in higher construction costs at a time when wages were already rising along with materials inflation. Concerns that the Biden Administration would compel pro-union corporate policies did deter some prospective manufacturing applicants, though I didn’t see it with mining and minerals refining projects.

I’ll note that, despite the Trump Administration immediately ripping up every DOE CBP and going out of its way to punish funding recipients embracing any social policy it deemed “too woke” (also stupid and counterproductive), it did recognize the importance of prior workforce development efforts. Many of these project elements were preserved and initiatives continued, albeit with different branding and without the pro-union posture.

Not everyone gets to be a winner

I’ve already criticized the Trump Administration (and Republicans generally) for excessive deference to Western US mining interests. The Biden approach, reflected primarily in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (a.k.a. “The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law” (BIL)) and CHIPS legislation, was to give every region of the country a stake in its economic agenda. The political thrust of that approach largely failed with Trump’s election, but I would argue also spread the proverbial peanut butter too thinly in terms of industry investments.

Not every region has the natural resources or existing industrial assets to play a significant role in certain sectors of the economy. Most mineral resources will never be economically viable; not everyone gets to be a hub for critical minerals processing. I’ll discuss these dynamics in greater depth, especially in my future posts on lithium and rare-earths.

The Biden Administration humored too much fantastical thinking about industries America had hardly started to build, when it needed real commercial beachheads. Some of this approach leaned on the traditional R&D funding model through universities and the national labs, but it also supplemented those smaller grants with workshops, listening sessions, and other publicized events intended to feel inclusive without a credible roadmap to commercialization.

Much of this was continuation of programming from prior administrations, but since President Biden was the first to take a big swing at commercial projects in the sector, I find it worth highlighting how his administration’s programming diluted efforts to solve for commercial challenges. It would have been better served focusing on higher-quality opportunities. Where statutory parameters on grant funds were an impediment, it should have worked with Congress to reprogram them.

Final thoughts

In an earlier draft of this post, I discussed at length the Trump Administration’s abuse of the FAST-41 Transparency Dashboard. It has been handing out FAST-41 designations like Halloween candy, mostly to signal extraordinary efforts in streamlining NEPA review. If you’re unfamiliar with FAST-41 and not a permitting wonk, I don’t necessarily recommend subjecting yourself to the headache of researching and trying to understand it.

I scrapped the section because I found the entire FAST-41 process and different categorizations (and impacts on NEPA reviews) to be too arcane and difficult to summarize efficiently. The important takeaway is we’re seeing the Trump Administration conflate what amounts to a signaling exercise (elevating as many projects as it can with FAST-41 designations) and tangible efforts to short-circuit NEPA review entirely. I already covered the risks of effectively skipping a proper NEPA review last week, so will leave it at that.

If you ask mproject developers which form of policy kayfabe they prefer, they’ll almost certainly tell you Trump’s. The Biden approach tried to empower workers and community stakeholders, to minimal commercial effect in mining and metals. Mostly headaches for federal funding applicants and ephemeral dreams.

The Trump approach lets them pump asset valuations in public markets with little to no effort. More to come on that front.

See you next week.

NOAA’s political leadership was aggressively pushing its role as a deep sea mining regulator from the start of 2025 as its way of building influence within the Trump Administration.

Data centers are now crowding out most other industrial activity, making access to power capacity and site infrastructure increasingly problematic.

Justice40 was a policy framework stipulating that at least 40% of all federal funding should benefit disadvantaged communities.

Many grant programs also carved out set-aside funding allocations for projects in qualified disadvantaged communities.