Is permitting obstructing American minerals security?

It’s complicated. (But probably not.)

This is the third post in Tailings, my series on minerals security in America. As I start to discuss specific projects and resources in my posts, I’ll add the disclaimer that these posts in no way constitute financial advice.

Permitting is a problem. But don’t let anyone tell you permitting is the problem.

The stars finally seem to be aligning for some measure of federal reform, though I’ll maintain a healthy dose of skepticism until I see it. In any case, I don’t intend to dig into specific proposals or speculate on their effects. There are much smarter people on these issues and reform efforts,1 so I’ll leave it to them to analyze and handicap legislation.

But the imperative is unmistakable, as a broad set of regulatory hurdles continue to snarl the energy infrastructure buildouts necessary to meet both parties’ industrial objectives. I’ve consistently seen permitting cited as a primary obstacle to recovering critical minerals. And I’m here to tell you that’s probably not true.

I can’t tell you how many times I heard a developer’s pitch include “and we’re already fully permitted” or “we’re on private lands and don’t need any federal approvals,” followed by a plea for federal financing assistance.

In a game of poker…that’s what we call a tell.

If you’re approaching the federal government about financing your project, permitting likely isn’t your problem. It’s project economics. If anything, because of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and other federal regulations, you’re exposing yourself to new potential headaches by pursuing federal funding.

And aside from developers of true world-class assets in gold, copper, iron, and other major commodities, just about everyone in American mining these days needs some form of federal financial assistance to make the math math.

I want to make this very clear up front. Permitting, NEPA reviews, and other avenues for adversarial litigation do impose time and financial cost burdens on project development. In some cases, severely. So before anyone comes back at me pointing at Resolution Copper or Pebble Mine, yes, I know America has its share projects that have been NIMBY’d into development hell.

But when we’re talking about the majority of designated critical minerals, regulatory hurdles are not a primary obstacle. Economics and US investor expectations for risk-adjusted returns on capital are far more problematic.

So why do we hear so much about permitting as an obstacle to minerals security?

The permitting bugbear, explained

Let’s first step back and clarify what we mean by “permitting,” since we see many local, state, and federal regulatory issues conflated in media.

There are actual land use and some environmental permits governed by state and local authorities. Then there are federal environmental permits, requiring compliance with statutes such as the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Endangered Species Act, and others. Finally, policymakers frequently conflate a whole host of regulatory issues ranging from labor laws and Tribal claims to historic and/or religious heritage, and throw them under the banner of “permitting.”

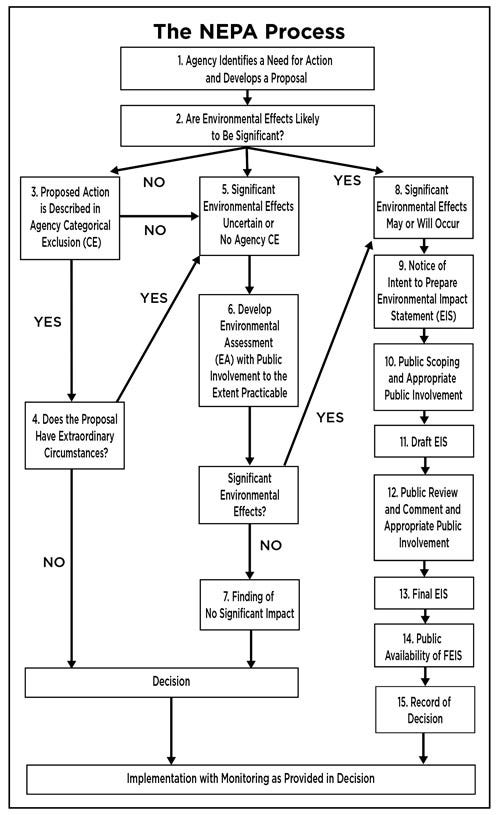

If a project is on federal lands (most of them west of the Rockies), is determined to impact protected assets (waters, endangered species habitats, historic sites, etc.), or receives federal funding, then the project requires a “major federal action” and NEPA review.2 The Trump Administration is taking as big a hatchet to these parameters as it can, but aside from addressing some risks of this approach, I don’t plan on discussing individual deregulatory actions (or their legality).

Ultimately, this collection of statutory and regulatory measures does produce industry frustrations and fuels rhetoric about creating long project timelines, uncertainty, and weaker returns on investment.

Industry frustrations and policy misdirection

The average time of mine development in the United States from inception to commissioning in the US has ballooned in recent decades to nearly 30 years. I don’t have the dataset available, but I imagine that eye-popping figure deserves a little additional context.

Mining exploration and development activity in the US has withered over the past decades. Few economically viable projects are in active development, and we see relatively low levels of investment in most early-stage projects. Many projects languish for years on shoestring budgets, with funding trickling in for exploration and development work. Only after a project can demonstrate its value to strategic or other deep-pocketed investors does it see the sort of cash infusions necessary to accelerate more expensive feasibility work, permitting, piloting, and qualification.

In other words, these long project timelines are a function of market structure.

I’ll cover process and capital raises in greater detail in a subsequent post, but to get a project from exploration to the start of construction, it needs favorable market conditions at multiple stages of project development to raise cash. Those dynamics speak to a mismatch between modern Western shareholder capitalism, mining project development needs, and our policy incentives.

So I’ll restate the question — why the obsessive focus on permitting with other greater structural issues at play?

Here are a few explanations:

Clearing various permitting hurdles does impose costs on projects even if all goes smoothly. It’s effort and timeline uncertainty developers would certainly prefer to minimize, though most of these activities are completed well before projects have raised necessary project financing to advance into construction.

Mining is a politically conservative industry. I don’t want to make this a political post, but this point is important for understanding a key influencer of our mineral policy discourse. Mining executives and operators have a cultural bias against regulation. Some of that is influenced by experience, but in many cases, they genuinely overestimate the extent to which regulations are impairing their projects, and prefer to blame government rather than structural weakness in their businesses.

Calls for deregulation and blaming (what are considered left-wing) obstacles to doing business resonate better with Republican policymakers than asking for subsidies. Increased geographic partisan sorting also means states with more federal lands and higher-quality mining assets are now overwhelmingly represented by Republican governors and federal legislators.

Some projects, particularly the big ones that draw national attention, genuinely do get ensnared in permitting or litigation hell.

To the Trump Administration’s credit, I saw a clear evolution in thinking over the past calendar year.

Early in 2025, its focus was almost entirely on deregulatory actions to “unleash” minerals projects. I got the sense most of the political appointees at agencies genuinely believed “cutting red tape” would kickstart mining projects because that’s what they were hearing from lobbyists (not the National Security Council (NSC), where appointees had real sector experience). That lobbying fed into ideological bias, and they largely ignored the experienced career staff trying to educate them otherwise.

While those efforts haven’t subsided (more on that next week), I saw more manpower and financial resources turned toward broken markets and other economic barriers to project financing as the year progressed. I could see a recognition at the NSC and interagency level that deregulation alone wouldn’t move the needle on administration objectives.

(Unfortunately, I also saw the Administration inflict considerable damage to our supply chain efforts by freezing grants, gutting supportive tax credits, and crippling markets for key demand drivers. But more on that another time…)

Why are critical minerals different

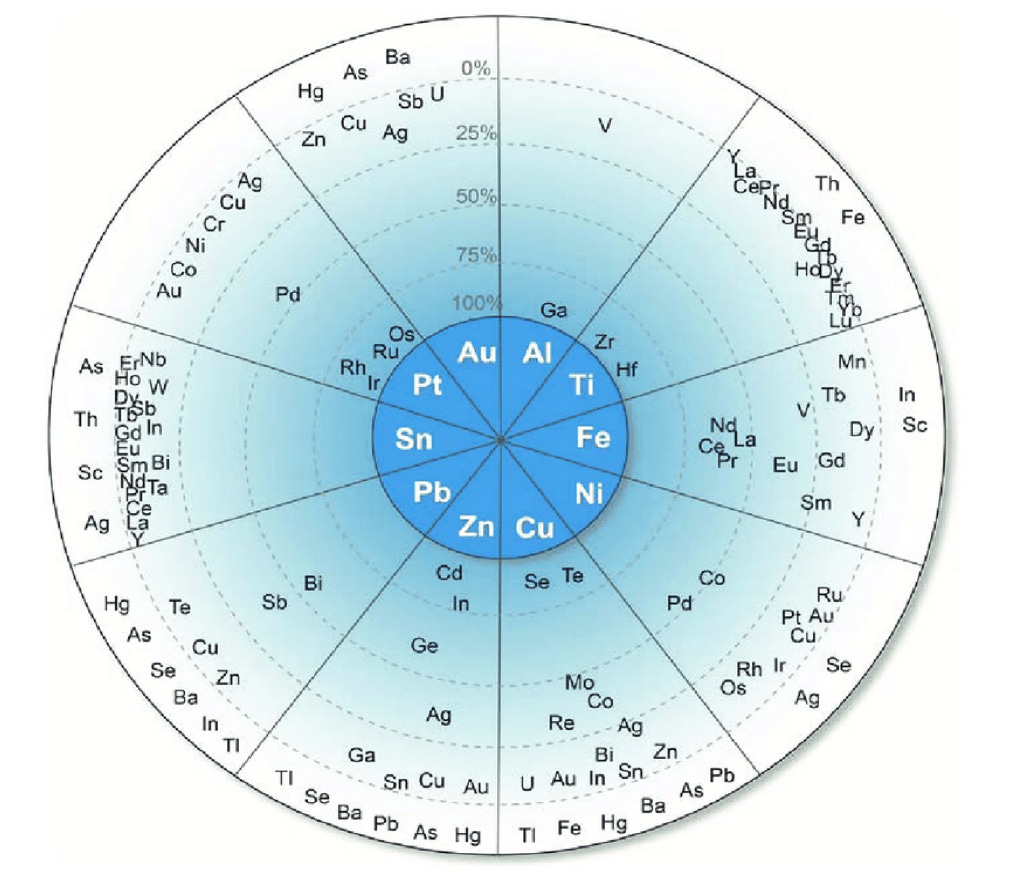

In last week’s post, I discussed some of the characteristics that set “critical minerals” apart from other mined materials.

By virtue of their susceptibility to Chinese manipulation or other highly volatile market dynamics, most critical minerals don’t operate on the sorts of natural supply-and-demand driven commodity cycles that base and precious metals do.3 As a result, we typically see critical minerals project developers fall into one of two categories:

Mining majors that determine the economics justify processing or selling tailings from a larger ore body to extract minerals they wouldn’t otherwise bother recovering.

Junior miners that believe they can capitalize on a niche market where the majors won’t play.

Take a run through any of the high profile mining projects that have endured decade-long legal and/or regulatory battles and you’ll notice they all have something in common: They’re almost all mines for precious or base metals. Huge projects with long mine lives. Massive footprints and enormous capital requirements. Project developers know the return on investment needs to be worthwhile if they’re going to endure a costly regulatory and litigation gauntlet.

But these mine developers in the US rarely put forth the time, money, or effort to explore feasibility of recovering lower volume metals. They’ll publicly market or float to the government their potential critical mineral recoveries from tailings, but don’t want to pay for what they consider relatively low value, high risk opportunities. Monetizing those tailings wouldn’t incur meaningful permitting burdens given existing site operations.

In the second group, sponsors have fewer resources, less margin for error, and typically spend much longer developing assets before construction activities, if they reach that point. Projects also often trade hands multiple times before construction. This is also where we tend to see mining-focused private equity shops and family offices play a larger role.

In both groups, capital is the ultimate constraint.

Adventures in lithium permitting

Lithium is one of the few minerals that sits somewhere in the middle of the two groups I described. It’s not a precious or base metal, but the US has large enough forecasted demand and sufficiently good (if unconventional) resources to justify large mine development.

Ernest Scheyder’s excellent book “The War Below” opens with the saga of a lithium miner Ioneer and its struggle against Tiehm's buckwheat. A single endangered flower, apparently fond of the lithium-rich soil at Ioneer’s Rhyolite Ridge site, forced the company through a ringer of highly-publicized legal and regulatory headaches that ultimately required site plan modifications and other extraordinary conservation efforts to clear a path to project construction.

Ioneer wasn’t alone in drawing litigation. Lithium Americas, which LPO also financed and is now nearly a year into construction on the Thacker Pass project, faced its own hurdles. A Navajo group sued during the mine’s development and claimed Thacker Pass would destroy its historic site. Piedmont Lithium (now Elevra, following a 2025 merger with Sayona Lithium), which withdrew both its projects from LPO’s application pipeline amidst reorganization of its business, found its Carolina Lithium mine and refinery project outside Charlotte, NC bogged down by zoning hurdles and fierce local opposition. Scheyder covered both of these projects in his book.4

But why is Lithium Americas currently the only commercial lithium mine in construction? Why is Tesla’s Corpus Christi plant the only standalone lithium refinery in construction? Chalk it up to timing and commercial factors.

Lithium projects had a tight window from 2021-2023 to secure major offtake and investment agreements while prices were soaring, demand growth charts looked like hockey sticks, and automakers were racing to secure long-term battery metals supply. Euphoria waned in 2024, and a bear market set in for much of 2025, before some green shoots emerged late in the year. Lithium Americas was the only developer to clear all commercial and financial hurdles before that window closed. And of course Tesla could finance from its own balance sheet.

One could argue that absent the delays incurred trying to accommodate a flower and its litigious NGO champions, Ioneer would have had an easier time fundraising and advancing through pre-construction project milestones when lithium prices were elevated, the US lithium-ion battery market had a stronger growth narrative, and joint venture partner Sibanye-Stillwater had more appetite to pursue the project.

While Carolina Lithium remains mired in local permitting fights, Piedmont Lithium cancelled its planned Tennessee Lithium refinery outright due to market conditions, despite being fully permitted. Even with all approvals in hand, Carolina Lithium would still face similar financing challenges as every other US lithium project.

That’s not to say these are unworthy projects, or won’t move forward, just that market conditions have turned unfavorable to developers. And that’s the case across the board, not just for those projects I named. Hopefully, rebounding lithium prices (they’ve roughly doubled since June) will re-stimulate investor interest and financing activities. Ioneer still managed to close their loan with LPO (no small feat, given the diligence entailed) and maintains an attractive debt financing package.

The window will open again, it’s just a question of when and how wide.

I’m planning a deep-dive post on lithium in the coming weeks, so won’t elaborate on market forces any further here, but will just note the ultimate barrier to final investment decision (FID) and construction for all of these projects is ultimately commercial and rooted in economic expectations, not permitting.

The obligatory rare-earths mention

Rare-earths are another exception, given the attention they’ve received since the 2010 crisis, and the incentive to develop domestic projects despite challenging economics. There’s long been an implicit assumption that policy support would materialize to subsidize and protect these projects on national security grounds.

Heavy rare-earth mining in particular is notoriously environmentally hazardous, and our regulations certainly create barriers to building mines in the US. But you also don’t see many folks on either side of the aisle arguing to bring this to America.

I’ll be doing a separate post on rare-earths, so will leave it there for now.

The risks of cutting corners

I saw toward the end of my tenure at DOE that the agency was grasping for legal arguments to determine NEPA wouldn’t apply to any projects it funds with grants or debt because the agency didn’t exert “significant control” over the project scope. Therefore, our funding wouldn’t constitute a “major action.” Public reporting has covered the move for LPO, though I’m not clear how it played out. I’m not a lawyer, and won’t weigh in on whether these are sound interpretations.

But I do see a risk with a federal agency declaring NEPA no longer applies to its projects. Especially when the political appointees responsible for pushing these policies have no experience delivering projects and don’t understand practical execution barriers.

A subsequent administration could simply say “no, NEPA does in fact apply to this project” and halt its progress.

Plaintiffs seeking to thwart projects may find greater success in the court system by arguing agencies skirted federal law.

Serious project developers will exercise more caution in exposing themselves to future legal risks, jeopardizing the project or exposing themselves to significant financial damages. I imagine those that believe they can move quickly to complete projects may bet on safe harbor from consequences from a future administration. But ultimately, the Administration is opening projects up to unnecessary risks they may regret embracing.

Projects may avoid hiring environmental consultants, but I never once saw a project at LPO held up by its NEPA review. Financing and other commercial conditions were always the final barriers to projects advancing into construction.

Final Thoughts

I truly don’t want to be dismissive of permitting as one barrier to project development and delivery. Every little bit of enabling policy helps, assuming we’re comfortable with the tradeoffs.

But just as YIMBY policymaking in cities can’t fix housing economics overnight, deregulating mining or streamlining permitting won’t alleviate the structural economic forces holding back project development.

Based on my experience, I lean to the deregulatory side and would like to see moderate legislative reforms reduce burdens on project developers. I simply don’t think aggressive reforms are necessary to achieve our national objectives and do carry significant risks of harm and blowback.

Reducing regulatory burdens would mitigate some uncertainty around project timelines and might incentivize investment at earlier project stages, with better line of sight to returns.

Mine developers might see adequate returns in smaller, less-complex projects with lower capital intensity. We want a more diverse mining ecosystem that isn’t just megaprojects.

It’s tough to know which federal laws and regulations pose the greatest threat to project delivery or which ones have the most support for loosening reforms.

We shouldn’t pretend deregulation is a salve for an atrophied domestic industry and apprehensive capital markets to address critical minerals challenges.

I had some family travel and other obligations that slowed my writing over the past week, and as a result I got this post out later than I’d hoped. To get myself back into an early-week release cadence and avoid another 3500+ word post, I split this one. Next week I’ll continue pulling at the permitting thread.

Deep sea mining, refinery siting, and more on tap!

Obligatory shoutout to Thomas Hochman at the Foundation for American Innovation. I don’t agree with him on everything, but he’s well-researched and sharp in his policy analysis. His Substack “Green Tape” is worth a follow.

NEPA is not a “permit” or “approval” per se, but rather a review process designed to ensure compliance with all necessary permits and completion of all necessary stakeholder consultations, depending on the scope and impact of a project.

Roughly a dozen designated critical minerals from the 2025 list are precious or base metals.

I convinced probably a dozen other colleagues to pick up “The War Below” after I finished it in early 2024, selling it to them as a “play-by-play of our critical minerals portfolio.”

The point about developers using 'fully permitted' as a selling point while asking for federal financing is such a good tell. I've seen this dynamic play out in clean tech too where the regulator blame game masks what are fundamentaly capital allocation problems. The lithium timing window you mentioned is interesting, reminds me of how solar manufacturing had a similar window around 2018-2019 that most domestic players missed. Curious whether the 30-year timeline figure accounts for projects that got shelved entirely during down cycles.

This is written by an ex-regulator, that’s for sure. As they say, “Never reason from a price change.” Or let’s try — “Never reason from a change in market structure.”

You cannot accept as given that project timelines have ballooned, uncertainty risen, and costs skyrocketed, and then ask whether—in light of all that—a few measly regulations are the problem.

Why? Well, the answer is already in your essay. You just need to take out the deflection and passive framing of your conclusion on regulatory burden. You say:

“Ultimately, this collection of statutory and regulatory measures does produce industry frustrations and fuels rhetoric about creating long project timelines, uncertainty, and weaker returns on investment.”

Here’s the rewrite, admitting that regulations actually do something, not just “fuel rhetoric”:

“Ultimately, this collection of statutory and regulatory measures frustrates industry and creates long project timelines, uncertainty, and weaker returns on investment.”

There you go. You have successfully gotten the order of operations right. Long timelines, uncertain funding, and bad finances are not some exogenous curse. They sit on top of the underlying problem—a convoluted and burdensome permitting and regulation scheme—that you want to wave away.